IELTS Online

IELTS Reading Cam 15 Test 1: Dịch đề & Giải đề chi tiết

Mục lục [Ẩn]

Cambridge 15 Test 1 là một trong những đề IELTS Reading được đánh giá có độ khó cao, thường gây khó khăn cho thí sinh ở phần từ vựng học thuật và dạng câu hỏi suy luận. Trong bài viết dưới đây, Langmaster sẽ cung cấp transcript đầy đủ, đáp án chi tiết kèm giải thích rõ ràng theo từng câu, giúp bạn hiểu cách làm bài, tránh bẫy thường gặp và nâng cao kỹ năng Reading một cách hiệu quả.

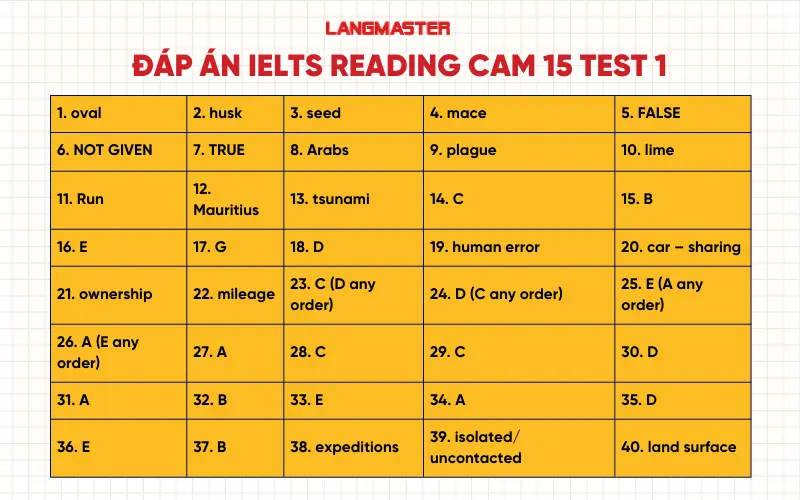

1. Đáp án IELTS Reading Cam 15 Test 1

|

1. oval |

2. husk |

3. seed |

4. mace |

5. FALSE |

|

6. NOT GIVEN |

7. TRUE |

8. Arabs |

9. plague |

10. lime |

|

11. Run |

12. Mauritius |

13. tsunami |

14. C |

15. B |

|

16. E |

17. G |

18. D |

19. human error |

20. car – sharing |

|

21. ownership |

22. mileage |

23. C (D any order) |

24. D (C any order) |

25. E (A any order) |

|

26. A (E any order) |

27. A |

28. C |

29. C |

30. D |

|

31. A |

32. B |

33. E |

34. A |

35. D |

|

36. E |

37. B |

38. expeditions |

39. isolated/ uncontacted |

40. land surface |

>> Xem thêm: Giải đề The study of chimpanzee culture IELTS Reading Actual Test Vol 6 Test 2

2. IELTS Reading Cam 15 Test 1 Passage 1: Nutmeg – a valuable spice

READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1–13 which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

|

Nutmeg – a valuable spice The nutmeg tree, Myristica fragrans, is a large evergreen tree native to Southeast Asia. Until the late 18th century, it only grew in one place in the world: a small group of islands in the Banda Sea, part of the Moluccas – or Spice Islands – in northeastern Indonesia. The tree is thickly branched with dense foliage of tough, dark green oval leaves, and produces small, yellow, bell–shaped flowers and pale yellow pear–shaped fruits. The fruit is encased in a fleshy husk. When the fruit is ripe, this husk splits into two halves along a ridge running the length of the fruit. Inside is a purple–brown shiny seed, 2–3 cm long by about 2.cm across, surrounded by a lacy red or crimson covering called an ‘aril’. These are the sources of the two spices nutmeg and mace, the former being produced from the dried seed and the latter from the aril. Nutmeg was a highly prized and costly ingredient in European cuisine in the Middle Ages, and was used as a flavouring, medicinal, and preservative agent. Throughout this period, the Arabs were the exclusive importers of the spice to Europe. They sold nutmeg for high prices to merchants based in Venice, but they never revealed the exact location of the source of this extremely valuable commodity. The Arab– Venetian dominance of the trade finally ended in 1512, when the Portuguese reached the Banda Islands and began exploiting its precious resources. Always in danger of competition from neighbouring Spain, the Portuguese began subcontracting their spice distribution to Dutch traders. Profits began to flow into the Netherlands, and the Dutch commercial fleet swiftly grew into one of the largest in the world. The Dutch quietly gained control of most of the shipping and trading of spices in Northern Europe. Then, in 1580, Portugal fell under Spanish rule, and by the end of the 16th century the Dutch found themselves locked out of the market. As prices for pepper, nutmeg, and other spices soared across Europe, they decided to fight back. In 1602, Dutch merchants founded the VOC, a trading corporation better known as the Dutch East India Company. By 1617, the VOC was the richest commercial operation in the world. The company had 50,000 employees worldwide, with a private army of 30,000 men and a fleet of 200 ships. At the same time, thousands of people across Europe were dying of the plague, a highly contagious and deadly disease. Doctors were desperate for a way to stop the spread of this disease, and they decided nutmeg held the cure. Everybody wanted nutmeg, and many were willing to spare no expense to have it. Nutmeg bought for a few pennies in Indonesia could be sold for 68,000 times its original cost on the streets of London. The only problem was the short supply. And that’s where the Dutch found their opportunity. The Banda Islands were ruled by local sultans who insisted on maintaining a neutral trading policy towards foreign powers. This allowed them to avoid the presence of Portuguese or Spanish troops on their soil, but it also left them unprotected from other invaders. In 1621, the Dutch arrived and took over. Once securely in control of the Bandas, the Dutch went to work protecting their new investment. They concentrated all nutmeg production into a few easily guarded areas, uprooting and destroying any trees outside the plantation zones. Anyone caught growing a nutmeg seedling or carrying seeds without the proper authority was severely punished. In addition, all exported nutmeg was covered with lime to make sure there was no chance a fertile seed which could be grown elsewhere would leave the islands. There was only one obstacle to Dutch domination. One of the Banda Islands, a sliver of land called Run, only 3km long by less than 1km wide, was under the control of the British. After decades of fighting for control of this tiny island, the Dutch and British arrived at a compromise settlement, the Treaty of Breda, in 1667. Intent on securing their hold over every nutmeg–producing island, the Dutch offered a trade: if the British would give them the island of Run, they would in turn give Britain a distant and much less valuable island in North America. The British agreed. That other island was Manhattan, which is how New Amsterdam became New York. The Dutch now had a monopoly over the nutmeg trade which would last for another century. Then, in 1770, a Frenchman named Pierre Poivre successfully smuggled nutmeg plants to safety in Mauritius, an island off the coast of Africa. Some of these were later exported to the Caribbean where they thrived, especially on the island of Grenada. Next, in 1778, a volcanic eruption in the Banda region caused a tsunami that wiped out half the nutmeg groves. Finally, in 1809, the British returned to Indonesia and seized the Banda Islands by force. They returned the islands to the Dutch in 1817, but not before transplanting hundreds of nutmeg seedlings to plantations in several locations across southern Asia, The Dutch nutmeg monopoly was over. Today, nutmeg is grown in Indonesia, the Caribbean, India, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and Sri Lanka, and world nutmeg production is estimated to average between 10,000 and 12,000 tonnes per year. |

Questions 1–4

Complete the notes below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 1–8 on your answer sheet.

The nutmeg tree and fruit

● the leaves of the tree are 1……………………. in shape

● the 2……………………. surrounds the fruit and breaks open when the fruit is ripe

● the 3……………………. is used to produce the spice nutmeg

● the covering known as the aril is used to produce 4……………………..

● the tree has yellow flowers and fruit

Questions 5–7

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 5–7 on your answer sheet, write

| TRUE | if the statement agrees with the information |

| FALSE | if the statement contradicts the information |

| NOT GIVEN | if there is no information on this |

5 In the Middle Ages, most Europeans knew where nutmeg was grown.

6 The VOC was the world’s first major trading company.

7 Following the Treaty of Breda, the Dutch had control of all the islands where nutmeg grew.

Questions 8–13

Complete the table below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 8–13 on your answer sheet.

|

Middle Ages |

Nutmeg was brought to Europe by the 8…………… |

|

16th century |

European nations took control of the nutmeg trade |

|

17th century |

Demand for nutmeg grew, as it was believed to be effective against the disease known as the 9…………… The Dutch – took control of the Banda Islands – restricted nutmeg production to a few areas – put 10…………… on nutmeg to avoid it being cultivated outside the islands – finally obtained the island of 11…………… from the British |

|

Late 18th century |

1770 – nutmeg plants were secretly taken to 12…………… 1778 – half the Banda Islands’ nutmeg plantations were destroyed by a 13…………… |

Trên đây là toàn bộ đề thi Cam 15 test 1 Passage 1: Nutmeg – a valuable spice, bạn có thể tham khảo bài dịch và giải thích đáp án chi tiết TẠI ĐÂY.

3. IELTS Reading Cam 15 Test 1 Passage 2: Driverless cars

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14–26 which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

|

Driverless cars A The automotive sector is well used to adapting to automation in manufacturing. The implementation of robotic car manufacture from the 1970s onwards led to significant cost savings and improvements in the reliability and flexibility of vehicle mass production. A new challenge to vehicle production is now on the horizon and, again, it comes from automation. However, this time it is not to do with the manufacturing process, but with the vehicles themselves. Research projects on vehicle automation are not new. Vehicles with limited self–driving capabilities have been around for more than 50 years, resulting in significant contributions towards driver assistance systems. But since Google announced in 2010 that it had been trialling self–driving cars on the streets of California, progress in this field has quickly gathered pace. B There are many reasons why technology is advancing so fast. One frequently cited motive is safety; indeed, research at the UK’s Transport Research Laboratory has demonstrated that more than 90 percent of road collisions involve human error as a contributory factor, and it is the primary cause in the vast majority. Automation may help to reduce the incidence of this. Another aim is to free the time people spend driving for other purposes. If the vehicle can do some or all of the driving, it may be possible to be productive, to socialise or simply to relax while automation systems have responsibility for safe control of the vehicle. If the vehicle can do the driving, those who are challenged by existing mobility models – such as older or disabled travellers – may be able to enjoy significantly greater travel autonomy. C Beyond these direct benefits, we can consider the wider implications for transport and society, and how manufacturing processes might need to respond as a result. At present, the average car spends more than 90 percent of its life parked. Automation means that initiatives for car–sharing become much more viable, particularly in urban areas with significant travel demand. If a significant proportion of the population choose to use shared automated vehicles, mobility demand can be met by far fewer vehicles. D The Massachusetts Institute of Technology investigated automated mobility in Singapore, finding that fewer than 30 percent of the vehicles currently used would be required if fully automated car sharing could be implemented. If this is the case, it might mean that we need to manufacture far fewer vehicles to meet demand. However, the number of trips being taken would probably increase, partly because empty vehicles would have to be moved from one customer to the next. Modelling work by the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute suggests automated vehicles might reduce vehicle ownership by 43 percent, but that vehicles’ average annual mileage double as a result. As a consequence, each vehicle would be used more intensively, and might need replacing sooner. This faster rate of turnover may mean that vehicle production will not necessarily decrease E Automation may prompt other changes in vehicle manufacture. If we move to a model where consumers are tending not to own a single vehicle but to purchase access to a range of vehicle through a mobility provider, drivers will have the freedom to select one that best suits their needs for a particular journey, rather than making a compromise across all their requirements. Since, for most of the time, most of the seats in most cars are unoccupied, this may boost production of a smaller, more efficient range of vehicles that suit the needs of individuals. Specialised vehicles may then be available for exceptional journeys, such as going on a family camping trip or helping a son or daughter move to university. F There are a number of hurdles to overcome in delivering automated vehicles to our roads. These include the technical difficulties in ensuring that the vehicle works reliably in the infinite range of traffic, weather and road situations it might encounter; the regulatory challenges in understanding how liability and enforcement might change when drivers are no longer essential for vehicle operation; and the societal changes that may be required for communities to trust and accept automated vehicles as being a valuable part of the mobility landscape. G It’s clear that there are many challenges that need to be addressed but, through robust and targeted research, these can most probably be conquered within the next 10 years. Mobility will change in such potentially significant ways and in association with so many other technological developments, such as telepresence and virtual reality, that it is hard to make concrete predictions about the future. However, one thing is certain: change is coming, and the need to be flexible in response to this will be vital for those involved in manufacturing the vehicles that will deliver future mobility. |

Questions 14–18

Reading Passage 2 has seven paragraphs, A–G.

Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A–G, in boxes 14–18 on your answer sheet.

14 reference to the amount of time when a car is not in use

15 mention of several advantages of driverless vehicles for individual road–users

16 reference to the opportunity of choosing the most appropriate vehicle for each trip

17 an estimate of how long it will take to overcome a number of problems

18 a suggestion that the use of driverless cars may have no effect on the number of vehicles manufactured

Questions 19–22

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 19–22 on your answer sheet.

|

The impact of driverless cars Figures from the Transport Research Laboratory indicate that most motor accidents are partly due to 19……………………., so the introduction of driverless vehicles will result in greater safety. In addition to the direct benefits of automation, it may bring other advantages. For example, schemes for 20………………………. will be more workable, especially in towns and cities, resulting in fewer cars on the road. According to the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, there could be a 43 percent drop in 21…………………….. of cars. However, this would mean that the yearly 22…………………….. of each car would, on average, be twice as high as it currently is. this would lead to a higher turnover of vehicles, and therefore no reduction in automotive manufacturing. |

Questions 23 and 24

Choose TWO letters, A–E.

Write the correct letters in boxes 23 and 24 on your answer sheet.

Which TWO benefits of automated vehicles does the writer mention?

A Car travellers could enjoy considerable cost savings.

B It would be easier to find parking spaces in urban areas.

C Travellers could spend journeys doing something other than driving.

D People who find driving physically difficult could travel independently.

E A reduction in the number of cars would mean a reduction in pollution.

Questions 25 and 26

Choose TWO letters, A–E.

Write the correct letters in boxes 25 and 26 on your answer sheet.

Which TWO challenges to automated vehicle development does the writer mention?

A making sure the general public has confidence in automated vehicles

B managing the pace of transition from conventional to automated vehicles

C deciding how to compensate professional drivers who become redundant

D setting up the infrastructure to make roads suitable for automated vehicles

E getting automated vehicles to adapt to various different driving conditions

Trên đây là toàn bộ đề thi Cam 15 test 1 Passage 2: Driverless cars, bạn có thể tham khảo bài dịch và giải thích đáp án chi tiết TẠI ĐÂY.

>> Xem thêm: Tổng hợp tài liệu luyện thi IELTS Reading miễn phí cơ bản đến nâng cao

4. IELTS Reading Cam 15 Test 1 Passage 3: What is exploration?

4.1. Đề bài

READING PASSAGE 3

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27–40 which are based on Reading Passage 3 below.

|

What is exploration? We are all explores. Our desire to discover, and then share that new–found knowledge, is part of what makes us human – indeed, this has played an important part in our success as a species. Long before the first caveman slumped down beside the fire and grunted news that there were plenty of wildebeest over yonder, our ancestors had learnt the value of sending out scouts to investigate the unknown. This questing nature of ours undoubtedly helped our species spread around the globe, just as it nowadays no doubt helps the last nomadic Penan maintain their existence in the depleted forests of Borneo, and a visitor negotiate the subways of New York. (Tất cả chúng ta đều là những nhà thám hiểm. Khát vọng khám phá rồi chia sẻ những tri thức mới tìm được là một phần bản chất làm nên con người – và trên thực tế, điều đó đã đóng vai trò quan trọng trong sự thành công của loài người như một giống loài. Từ rất lâu trước khi người tiền sử đầu tiên ngồi phịch xuống bên đống lửa và gầm gừ thông báo rằng phía bên kia có rất nhiều linh dương đầu bò, tổ tiên của chúng ta đã học được giá trị của việc cử những người đi trinh sát để thăm dò những điều chưa biết. Bản năng ưa tìm tòi này chắc chắn đã giúp loài người lan rộng khắp địa cầu; cũng giống như ngày nay, nó giúp những người Penan du mục cuối cùng duy trì sự tồn tại của họ trong những khu rừng cạn kiệt ở Borneo, hay giúp một du khách xoay xở trong hệ thống tàu điện ngầm của New York.) Over the years, we’ve come to think of explorers as a peculiar breed – different from the rest of us, different from those of us who are merely ‘well travelled’, even; and perhaps there is a type of person more suited to seeking out the new, a type of caveman more inclined to risk venturing out. That, however, doesn’t take away from the fact that we all have this enquiring instinct, even today; and that in all sorts of professions – whether artist, marine biologist or astronomer – borders of the unknown are being tested each day. (Theo thời gian, chúng ta dần xem các nhà thám hiểm như một kiểu người đặc biệt – khác với phần còn lại của chúng ta, khác cả với những người chỉ đơn thuần là “đi nhiều nơi”. Có lẽ quả thật tồn tại một kiểu người phù hợp hơn với việc tìm kiếm cái mới, một kiểu người tiền sử sẵn sàng chấp nhận rủi ro để bước ra ngoài. Tuy nhiên, điều đó không phủ nhận thực tế rằng ai trong chúng ta cũng mang bản năng tò mò ấy, ngay cả ngày nay; và trong vô số ngành nghề – từ nghệ sĩ, nhà sinh học biển đến nhà thiên văn học – những ranh giới của điều chưa biết vẫn đang được thử thách mỗi ngày.) Thomas Hardy set some of his novels in Egdon Heath, a fictional area of uncultivated land, and used the landscape to suggest the desires and fears of his characters. He is delving into matters we all recognise because they are common to humanity. This is surely an act of exploration, and into a world as remote as the author chooses. Explorer and travel writer Peter Fleming talks of the moment when the explorer returns to the existence he has left behind with his loved ones. The traveller ‘who has for weeks or months seen himself only as a puny and irrelevant alien crawling laboriously over a country in which he has no roots and no background, suddenly encounters his other self, a relatively solid figure, with a place in the minds of certain people’. (Thomas Hardy đã đặt bối cảnh cho một số tiểu thuyết của mình tại Egdon Heath, một vùng đất hoang dã hư cấu, và sử dụng cảnh quan để gợi lên những khát vọng và nỗi sợ của các nhân vật. Ông đi sâu vào những vấn đề mà ai cũng có thể nhận ra, bởi chúng là những điều chung của nhân loại. Điều này, chắc chắn, cũng là một hành vi thám hiểm – một cuộc thám hiểm vào thế giới xa xôi đến mức mà tác giả lựa chọn. Nhà thám hiểm và nhà văn du ký Peter Fleming từng nói về khoảnh khắc khi người thám hiểm quay trở lại cuộc sống mà anh ta đã rời bỏ, bên những người thân yêu. Người lữ hành, “sau nhiều tuần hoặc nhiều tháng chỉ thấy bản thân mình như một kẻ xa lạ nhỏ bé, vô nghĩa, lê bước nhọc nhằn trên một vùng đất nơi anh ta không có gốc rễ hay bối cảnh nào, bỗng chốc đối diện với một cái tôi khác – một hình ảnh vững vàng hơn, có vị trí trong tâm trí của những người nhất định”.) In this book about the exploration of the earth’s surface, I have confined myself to those whose travels were real and who also aimed at more than personal discovery. But that still left me with another problem: the word ‘explorer’ has become associated with a past era. We think back to a golden age, as if exploration peaked somehow in the 19th century – as if the process of discovery is now on the decline, though the truth is that we have named only one and a half million of this planet’s species, and there may be more than 10 million – and that’s not including bacteria. We have studied only 5 per cent of the species we know. We have scarcely mapped the ocean floors, and know even less about ourselves; we fully understand the workings of only 10 per cent of our brains. (Trong cuốn sách này, viết về việc khám phá bề mặt Trái Đất, tôi giới hạn đối tượng của mình ở những người có các chuyến đi là thật, và những người nhắm tới nhiều hơn là sự khám phá cá nhân. Tuy nhiên, điều đó vẫn để lại cho tôi một vấn đề khác: từ “nhà thám hiểm” ngày nay thường gắn liền với một thời đại đã qua. Chúng ta nghĩ về một “thời kỳ hoàng kim”, như thể việc thám hiểm đã đạt đỉnh vào thế kỷ 19 – như thể quá trình khám phá giờ đang suy tàn. Nhưng sự thật là chúng ta mới chỉ đặt tên cho khoảng 1,5 triệu loài sinh vật trên hành tinh này, trong khi con số thực tế có thể vượt quá 10 triệu loài – chưa kể vi khuẩn. Chúng ta mới chỉ nghiên cứu 5% số loài đã biết; gần như chưa lập bản đồ đáy đại dương; và còn hiểu về chính bản thân mình ít hơn nữa – chúng ta chỉ thực sự hiểu cách hoạt động của 10% bộ não.) Here is how some of today’s ‘explorers’ define the word. Ran Fiennes, dubbed the ‘greatest living explorer’, said, ‘An explorer is someone who has done something that no human has done before – and also done something scientifically useful.’ Chris Bonington, a leading mountaineer, felt exploration was to be found in the act of physically touching the unknown: ‘You have to have gone somewhere new.’ Then Robin Hanbury–Tenison, a campaigner on behalf of remote so–called ‘tribal’ peoples, said, ‘A traveller simply records information about some far–off world, and reports back; but an explorer changes the world.’ Wilfred Thesiger, who crossed Arabia’s Empty Quarter in 1946, and belongs to an era of unmechanised travel now lost to the rest of us, told me, ‘If I’d gone across by camel when I could have gone by car, it would have been a stunt.’ To him, exploration meant bringing back information from a remote place regardless of any great self–discovery. (Dưới đây là cách một số “nhà thám hiểm” ngày nay định nghĩa khái niệm này. Ran Fiennes, được mệnh danh là “nhà thám hiểm vĩ đại nhất còn sống”, cho rằng: “Nhà thám hiểm là người làm được điều mà chưa con người nào từng làm – và đồng thời mang lại giá trị khoa học.” Chris Bonington, một nhà leo núi hàng đầu, lại tin rằng thám hiểm nằm ở hành động chạm vào điều chưa biết về mặt vật lý: “Bạn phải đặt chân đến một nơi hoàn toàn mới.” Trong khi đó, Robin Hanbury–Tenison, người vận động vì quyền lợi của các cộng đồng ‘bộ lạc’ xa xôi, nói: “Một du khách chỉ ghi lại thông tin về một thế giới xa lạ rồi báo cáo lại; còn một nhà thám hiểm thì làm thay đổi thế giới.” Wilfred Thesiger, người đã băng qua sa mạc Empty Quarter của Ả Rập năm 1946 – thuộc về một thời kỳ du hành không cơ giới hóa nay đã mất – từng nói với tôi rằng: “Nếu tôi đi bằng lạc đà khi đã có thể đi bằng ô tô, thì đó chỉ là một màn phô trương.” Với ông, thám hiểm là việc mang thông tin trở về từ một nơi xa xôi, bất kể có sự khám phá bản thân hay không.) Each definition is slightly different – and tends to reflect the field of endeavour of each pioneer. It was the same whoever I asked: the prominent historian would say exploration was a thing of the past, the cutting–edge scientist would say it was of the present. And so on. They each set their own particular criteria; the common factor in their approach being that they all had, unlike many of us who simply enjoy travel or discovering new things, both a very definite objective from the outset and also a desire to record their findings. (Mỗi định nghĩa đều hơi khác nhau – và có xu hướng phản ánh lĩnh vực hoạt động của từng người tiên phong. Điều này giống nhau với bất kỳ ai tôi hỏi: nhà sử học nổi tiếng sẽ cho rằng thám hiểm là chuyện của quá khứ, còn nhà khoa học tiên phong lại khẳng định nó thuộc về hiện tại. Ai cũng đặt ra những tiêu chí riêng; điểm chung trong cách tiếp cận của họ là: không giống nhiều người trong chúng ta chỉ thích du lịch hay khám phá những điều mới lạ, họ đều có mục tiêu rõ ràng ngay từ đầu và mong muốn ghi chép, lưu lại những phát hiện của mình.) I’d best declare my own bias. As a writer, I’m interested in the exploration of ideas. I’ve done a great many expeditions and each one was unique. I’ve lived for months alone with isolated groups of people all around the world, even two ‘uncontacted tribes’. But none of these things is of the slightest interest to anyone unless, through my books, I’ve found a new slant, explored a new idea. Why? Because the world has moved on. The time has long passed for the great continental voyages – another walk to the poles, another crossing of the Empty Quarter. We know how the land surface of our planet lies; exploration of it is now down to the details – the habits of microbes, say, or the grazing behaviour of buffalo. Aside from the deep sea and deep underground, it’s the era of specialists. However, this is to disregard the role the human mind has in conveying remote places; and this is what interests me: how a fresh interpretation, even of a well–travelled route, can give its readers new insights. (Có lẽ tôi nên thừa nhận thiên kiến cá nhân của mình. Là một nhà văn, tôi quan tâm đến sự thám hiểm của ý tưởng. Tôi đã tham gia rất nhiều chuyến thám hiểm, và mỗi chuyến đều độc nhất. Tôi đã sống hàng tháng trời một mình với những cộng đồng biệt lập trên khắp thế giới, thậm chí cả với hai “bộ lạc chưa từng tiếp xúc”. Nhưng tất cả những điều đó sẽ không có chút ý nghĩa nào nếu, thông qua sách vở, tôi không tìm ra được một góc nhìn mới, không khám phá được một ý tưởng mới. Vì sao? Bởi thế giới đã thay đổi. Thời đại của những chuyến hải trình vĩ đại đã qua từ lâu – thêm một cuộc đi bộ đến hai cực, hay một lần nữa băng qua Empty Quarter. Chúng ta đã biết bề mặt Trái Đất ra sao; việc thám hiểm giờ đây nằm ở những chi tiết nhỏ – như tập tính của vi sinh vật, hay hành vi gặm cỏ của trâu bò. Ngoài đại dương sâu thẳm và lòng đất sâu, đây là kỷ nguyên của các chuyên gia. Tuy nhiên, cách nhìn này lại bỏ qua vai trò của tâm trí con người trong việc truyền tải những vùng đất xa xôi; và chính điều đó mới là thứ khiến tôi hứng thú: làm thế nào một cách diễn giải mới mẻ, ngay cả với một con đường đã được đi nhiều lần, vẫn có thể mang lại cho người đọc những nhận thức hoàn toàn mới.) |

Questions 27–32

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 27–32 on your answer sheet.

27 The writer refers to visitors to New York to illustrate the point that

A exploration is an intrinsic element of being human.

B most people are enthusiastic about exploring.

C exploration can lead to surprising results.

D most people find exploration daunting.

28 According to the second paragraph, what is the writer’s view of explorers?

A Their discoveries have brought both benefits and disadvantages.

B Their main value is in teaching others.

C They act on an urge that is common to everyone.

D They tend to be more attracted to certain professions than to others.

29 The writer refers to a description of Egdon Heath to suggest that

A Hardy was writing about his own experience of exploration.

B Hardy was mistaken about the nature of exploration.

C Hardy’s aim was to investigate people’s emotional states.

D Hardy’s aim was to show the attraction of isolation.

30 In the fourth paragraph, the writer refers to ‘a golden age’ to suggest that

A the amount of useful information produced by exploration has decreased.

B fewer people are interested in exploring than in the 19th century.

C recent developments have made exploration less exciting.

D we are wrong to think that exploration is no longer necessary.

31 In the sixth paragraph, when discussing the definition of exploration, the writer argues that

A people tend to relate exploration to their own professional interests.

B certain people are likely to misunderstand the nature of exploration.

C the generally accepted definition has changed over time.

D historians and scientists have more valid definitions than the general public.

32 In the last paragraph, the writer explains that he is interested in

A how someone’s personality is reflected in their choice of places to visit.

B the human ability to cast new light on places that may be familiar.

C how travel writing has evolved to meet changing demands.

D the feelings that writers develop about the places that they explore.

Questions 33–37

Look at the following statements (Questions 33–37) and the list of explorers below.

Match each statement with the correct explorer, A–E.

Write the correct letter, A–E, in boxes 33–37 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

33 He referred to the relevance of the form of transport used.

34 He described feelings on coming back home after a long journey.

35 He worked for the benefit of specific groups of people.

36 He did not consider learning about oneself an essential part of exploration.

37 He defined exploration as being both unique and of value to others.

List of Explorers

A Peter Fleming

B Ran Fiennes

C Chris Bonington

D Robin Hanbury–Tenison

E Wilfred Thesiger

Questions 38–40

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 38–40 on your answer sheet.

|

The writer’s own bias The writer has experience of a large number of 38………………., and was the first stranger that certain previously 39………………… people had encountered. He believes there is no need for further exploration of Earth’s 40…………………., except to answer specific questions such as how buffalo eat. |

>> Xem thêm: Thời gian làm Reading IELTS: Chiến lược phân bổ và mẹo làm bài hiệu quả

4.2. Đáp án IELTS Reading Cam 15 Test 1 Passage 3

Question 27: A

Thông tin trong bài: “This questing nature of ours undoubtedly helped our species spread around the globe, just as it nowadays no doubt helps the last nomadic Penan maintain their existence in the depleted forests of Borneo, and a visitor negotiate the subways of New York.”

Giải thích: Ví dụ về một du khách xoay xở trong hệ thống tàu điện ngầm New York được đưa ra song song với các ví dụ mang tính sinh tồn của loài người trong lịch sử. Điều này cho thấy bản năng khám phá không chỉ tồn tại trong những chuyến đi vĩ đại hay môi trường hoang dã, mà còn hiện diện trong các hoạt động thường ngày của con người hiện đại. Qua đó, tác giả nhấn mạnh rằng khám phá là một yếu tố bản chất, vốn có trong con người, chứ không phải là hành vi đặc biệt của một số ít cá nhân. Vì vậy, đáp án A là phù hợp nhất.

Question 28: C

Thông tin trong bài: “That, however, doesn’t take away from the fact that we all have this enquiring instinct, even today; and that in all sorts of professions … borders of the unknown are being tested each day.”

Giải thích: Đoạn văn khẳng định dù xã hội thường xem các nhà thám hiểm là những người đặc biệt, nhưng thực tế bản năng tìm tòi, khám phá tồn tại ở tất cả mọi người. Các nhà thám hiểm chỉ là những người hành động mạnh mẽ hơn dựa trên một thôi thúc vốn phổ quát. Do đó, quan điểm của tác giả là các nhà thám hiểm hành động dựa trên bản năng chung của toàn nhân loại, chứ không phải sở hữu một phẩm chất hoàn toàn khác biệt. Điều này khớp chính xác với lựa chọn C.

Question 29: C

Thông tin trong bài: “He is delving into matters we all recognise because they are common to humanity.”

Giải thích: Việc nhắc đến Egdon Heath không nhằm mô tả một chuyến thám hiểm địa lý, mà để minh họa cho cách Thomas Hardy sử dụng cảnh quan nhằm khai thác những cảm xúc, khát vọng và nỗi sợ mang tính phổ quát của con người. Tác giả coi đây là một dạng khám phá – khám phá nội tâm và trạng thái cảm xúc của con người. Vì vậy, mục đích của Hardy là nghiên cứu thế giới cảm xúc, không phải sự cô lập hay trải nghiệm cá nhân. Đáp án C là chính xác.

Question 30: D

Thông tin trong bài: “We think back to a golden age, as if exploration peaked somehow in the 19th century – as if the process of discovery is now on the decline, though the truth is that we have named only one and a half million of this planet’s species…”

Giải thích: Khái niệm “thời kỳ hoàng kim” được đưa ra để phản bác suy nghĩ sai lầm rằng thám hiểm đã kết thúc. Ngay sau đó, tác giả liệt kê hàng loạt dẫn chứng cho thấy kiến thức của con người về Trái Đất và chính bản thân mình vẫn còn vô cùng hạn chế. Điều này chứng minh rằng việc khám phá vẫn cần thiết và chưa hề hoàn tất. Vì vậy, đáp án D – cho rằng con người đang sai khi nghĩ thám hiểm không còn cần thiết – là lựa chọn đúng.

Question 31: A

Thông tin trong bài: “Each definition is slightly different – and tends to reflect the field of endeavour of each pioneer.”

Giải thích: Tác giả nhận xét rằng mỗi nhà thám hiểm định nghĩa “khám phá” theo cách khác nhau, và sự khác biệt này phản ánh lĩnh vực chuyên môn và mối quan tâm nghề nghiệp của từng người. Điều này cho thấy quan niệm về khám phá mang tính chủ quan, gắn liền với trải nghiệm cá nhân. Do đó, lập luận chính là con người thường liên hệ khám phá với lợi ích và ngành nghề của chính mình, phù hợp với đáp án A.

Question 32: B

Thông tin trong bài: “…how a fresh interpretation, even of a well–travelled route, can give its readers new insights.”

Giải thích: Ở đoạn cuối, tác giả khẳng định điều hấp dẫn nhất không còn là những vùng đất chưa ai đặt chân tới, mà là khả năng của trí óc con người trong việc mang lại cách nhìn mới cho những nơi đã quen thuộc. Trọng tâm nằm ở sự diễn giải và nhận thức, không phải địa điểm hay cảm xúc cá nhân. Do đó, đáp án B phản ánh chính xác mối quan tâm của tác giả.

Question 33: E

Thông tin trong bài: “If I’d gone across by camel when I could have gone by car, it would have been a stunt.”

Giải thích: Wilfred Thesiger trực tiếp đề cập đến phương tiện di chuyển và cho rằng lựa chọn hình thức di chuyển không phù hợp sẽ làm mất đi ý nghĩa của thám hiểm. Vì vậy, đáp án E là chính xác.

Question 34: A

Thông tin trong bài: “the moment when the explorer returns to the existence he has left behind with his loved ones.”

Giải thích: Peter Fleming mô tả rõ cảm xúc khi quay trở lại cuộc sống cũ sau một hành trình dài, nhấn mạnh sự đối diện giữa hai “cái tôi”. Điều này hoàn toàn phù hợp với nội dung câu hỏi.

Question 35: D

Thông tin trong bài: “a campaigner on behalf of remote so–called ‘tribal’ peoples”

Giải thích: Robin Hanbury–Tenison được mô tả là người vận động vì lợi ích của các cộng đồng bộ lạc xa xôi, tức là làm việc vì những nhóm người cụ thể. Do đó, đáp án D là đúng.

Question 36: E

Thông tin trong bài: “To him, exploration meant bringing back information from a remote place regardless of any great self–discovery.”

Giải thích: Wilfred Thesiger cho rằng khám phá bản thân không phải yếu tố thiết yếu của thám hiểm; điều quan trọng là thu thập và mang thông tin trở về. Điều này khớp hoàn toàn với yêu cầu của câu hỏi.

Question 37: B

Thông tin trong bài: “An explorer is someone who has done something that no human has done before – and also done something scientifically useful.”

Giải thích: Ran Fiennes nhấn mạnh hai tiêu chí: tính độc nhất và giá trị đối với người khác (khoa học). Đây chính là nội dung của câu hỏi, vì vậy đáp án B là chính xác.

Question 38: expeditions

Thông tin trong bài: “I’ve done a great many expeditions and each one was unique.”

Giải thích: Danh từ “expeditions” mô tả chính xác trải nghiệm của tác giả, phù hợp với yêu cầu điền từ.

Question 39: isolated / uncontacted

Thông tin trong bài: “I’ve lived for months alone with isolated groups of people all around the world, even two ‘uncontacted tribes’.”

Giải thích: Cả “isolated” và “uncontacted” đều xuất hiện trong đoạn văn và đều phù hợp về mặt ngữ nghĩa cũng như giới hạn số từ.

Question 40: land surface

Thông tin trong bài: “We know how the land surface of our planet lies; exploration of it is now down to the details…”

Giải thích: Tác giả khẳng định không cần tiếp tục khám phá bề mặt đất liền của Trái Đất ở quy mô lớn, mà chỉ cần nghiên cứu các chi tiết cụ thể. Vì vậy, “land surface” là đáp án chính xác.

>> Xem thêm: Những sai lầm khi luyện IELTS Reading cần tránh và cách khắc phục

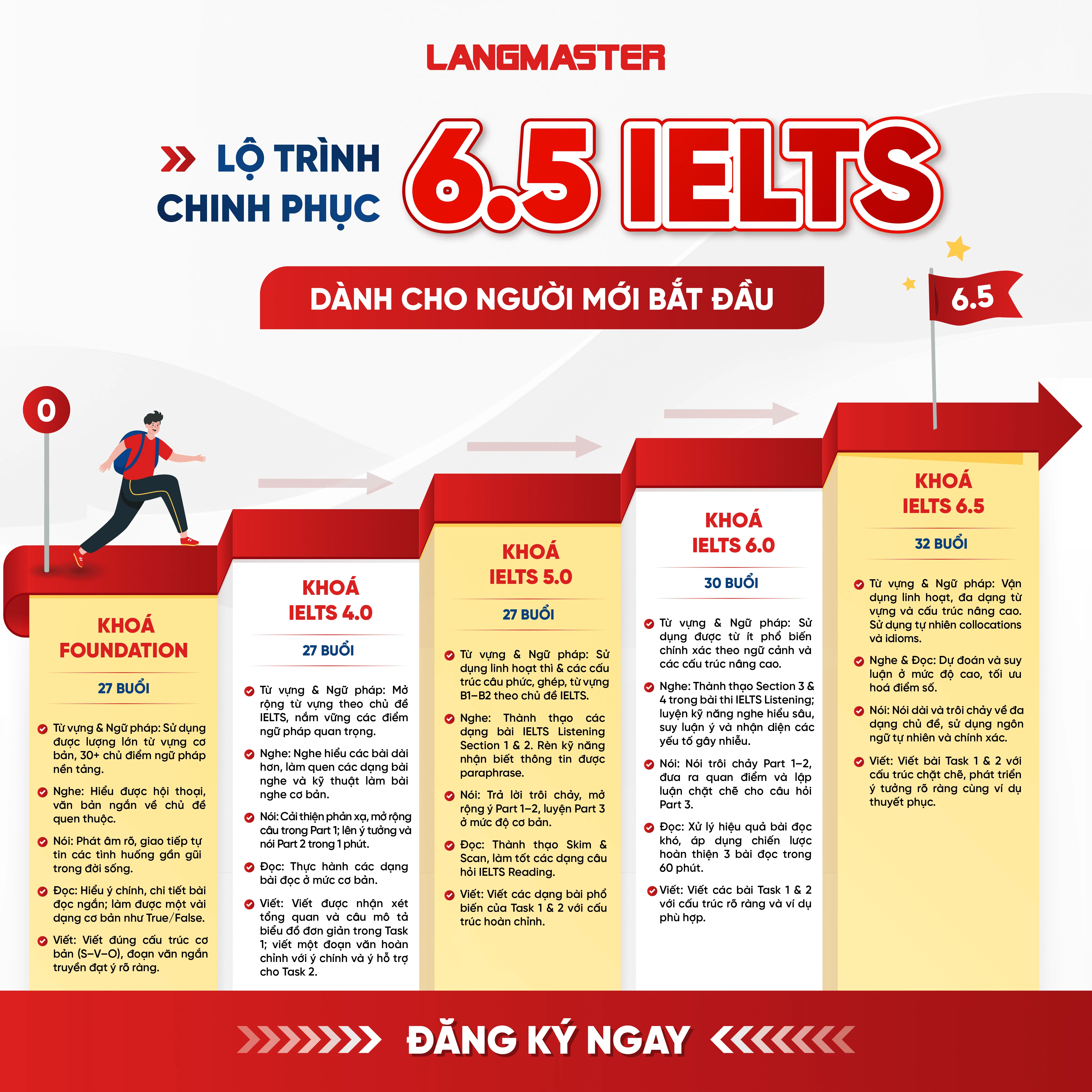

5. Khoá học IELTS Online tại Langmaster

IELTS Reading tưởng chừng là kỹ năng dễ tiếp cận, nhưng thực tế lại khiến nhiều thí sinh mất điểm vì đọc lướt, hiểu sai câu hỏi và dễ mắc bẫy paraphrase tinh vi. Nguyên nhân chủ yếu xuất phát từ việc thiếu tư duy đọc học thuật và chưa nắm rõ logic ra đề. Trong số các lựa chọn hiện nay, Langmaster được đánh giá là một trong những trung tâm đào tạo IELTS uy tín hàng đầu với phương pháp giảng dạy bài bản, không chỉ giúp người học cải thiện Reading một cách bền vững mà còn phát triển đồng đều cả Listening, Speaking và Writing, hướng tới mục tiêu nâng cao năng lực sử dụng tiếng Anh toàn diện.

Ưu điểm nổi bật của khóa học IELTS Online tại Langmaster:

-

Mô hình sĩ số nhỏ (7–10 học viên): Tăng cường tương tác hai chiều, giúp giảng viên theo sát từng học viên và điều chỉnh phương pháp giảng dạy phù hợp với tiến độ cá nhân.

-

Coaching 1:1 cùng chuyên gia: Học viên được hỗ trợ chuyên sâu để khắc phục điểm yếu cụ thể, từ đó tối ưu chiến lược làm bài và cải thiện band điểm hiệu quả.

-

Lộ trình học cá nhân hóa theo mục tiêu band: Dựa trên bài đánh giá đầu vào, chương trình được thiết kế sát với trình độ và mục tiêu của từng học viên, giúp học đúng trọng tâm và tiết kiệm thời gian.

-

Chấm chữa chi tiết trong 24h bởi giảng viên IELTS 7.5+: Giúp học viên nhận diện rõ lỗi sai, cải thiện độ chính xác và nâng cao sự tự tin khi sử dụng tiếng Anh.

-

Thi thử chuẩn format đề thi thật: Giúp học viên làm quen với áp lực phòng thi, rèn luyện khả năng phản xạ và kiểm soát thời gian hiệu quả.

-

Học online với hệ sinh thái hỗ trợ đầy đủ và cam kết đầu ra bằng văn bản: Đảm bảo chất lượng học tập tương đương offline và lộ trình chinh phục band điểm rõ ràng, minh bạsch.

Đăng ký học thử IELTS Online tại Langmaster ngay hôm nay để bắt đầu hành trình chinh phục mục tiêu IELTS của bạn

Nội Dung Hot

KHÓA TIẾNG ANH GIAO TIẾP 1 KÈM 1

- Học và trao đổi trực tiếp 1 thầy 1 trò.

- Giao tiếp liên tục, sửa lỗi kịp thời, bù đắp lỗ hổng ngay lập tức.

- Lộ trình học được thiết kế riêng cho từng học viên.

- Dựa trên mục tiêu, đặc thù từng ngành việc của học viên.

- Học mọi lúc mọi nơi, thời gian linh hoạt.

KHÓA HỌC IELTS ONLINE

- Sĩ số lớp nhỏ (7-10 học viên), đảm bảo học viên được quan tâm đồng đều, sát sao.

- Giáo viên 7.5+ IELTS, chấm chữa bài trong vòng 24h.

- Lộ trình cá nhân hóa, coaching 1-1 cùng chuyên gia.

- Thi thử chuẩn thi thật, phân tích điểm mạnh - yếu rõ ràng.

- Cam kết đầu ra, học lại miễn phí.

KHÓA TIẾNG ANH TRẺ EM

- Giáo trình Cambridge kết hợp với Sách giáo khoa của Bộ GD&ĐT hiện hành

- 100% giáo viên đạt chứng chỉ quốc tế IELTS 7.0+/TOEIC 900+

- X3 hiệu quả với các Phương pháp giảng dạy hiện đại

- Lộ trình học cá nhân hóa, con được quan tâm sát sao và phát triển toàn diện 4 kỹ năng

Bài viết khác

Các dạng bài phổ biến và tiêu chí chấm điểm IELTS Reading chi tiết nhất: Multiple Choice, Matching Information, Matching Headings,... và hướng dẫn chiến lược làm bài hiệu quả

Những sai lầm khi luyện IELTS Reading bao gồm: dịch từng từ, đọc hết cả bài, không đọc câu hỏi trước, không quản lý thời gian, không nắm vững kỹ năng paraphrase, viết sai chính tả

![Giải đề IELTS Reading: A brief history of humans and food [full answers]](https://langmaster.edu.vn/storage/images/2025/09/20/a-brief-history-of-humans-and-food-ielts-reading-answers.webp)

Giải đề thi IELTS Reading “A brief history of humans and food” kèm full đề thi thật, câu hỏi, đáp án, giải thích chi tiết, và từ vựng cần lưu ý khi làm bài.

Tổng hợp IELTS Reading tips hay nhất giúp bạn đọc nhanh, nắm ý chính và xử lý thông tin chính xác, tự tin đạt điểm cao trong kỳ thi IELTS.

![Giải đề IELTS Reading: The importance of law [Full answers]](https://langmaster.edu.vn/storage/images/2025/09/22/55.webp)

Giải đề IELTS Reading “The importance of law” kèm đáp án chi tiết, từ vựng quan trọng và bí quyết luyện thi hiệu quả để nâng cao band điểm.

.png)

.png)

![Giải Cam IELTS 15, Test 1, Reading Passage 1: Nutmeg - a valuable spice [FULL ANSWERS]](https://langmaster.edu.vn/storage/uploads/original/2026/01/21/nutmeg-a-valuable-spice-reading-answers (1).png)

.png)

.png)